by Dan Roberts, Lead Instructor

Not one of them

is like another.

Don’t ask us why.

Go ask your mother.

– Dr. Seuss

Think back to when you were learning your first object-oriented programming language. If you learned to program in the last 15 years, there’s a good chance that was your first language, period. You probably started off with simple concepts like conditionals and loops, moved on to methods, and then to classes. And then at some point your instructor (or mentor or tutorial video) introduced a concept called inheritance.

If you’re like me, your first exposure to inheritance was a bit of a mess. Maybe you couldn’t quite get a handle on the syntax. Or maybe you were able to make it work on the class project and pass the exam, but couldn’t quite figure out where you would ever use this in the real world. And then once that introductory course was over, you probably packed inheritance back up into your mental toolbox and didn’t use it again for a long time.

The fact is, inheritance is complicated. It’s hard to use correctly, even for experienced engineers – it took me several years in industry before I felt like I had a good handle on the subject. Yet inheritance is a tool with first-class support in most modern languages, and which is taught to many novice programmers almost immediately.

In this blog post I’ll dive into why teaching inheritance is hard, some of the problems with current methods, and what Ada Developers Academy is doing to try and address this problem.

Do We Need Inheritance?

The first question we should ask is, “do we really need to teach inheritance?” This might seem like a silly question – everyone teaches inheritance, it’s a key part of object-oriented programming! However time is a scarce resource in a program like Ada’s, and everything we do teach means there’s something else we don’t teach. We’ve found more often than you might expect that we can drop something that “everyone” does, and end up with a leaner curriculum that is more valuable to both our students and their employers.

But as it turns out, we do need to teach inheritance. This is due to the way we leverage frameworks like Ruby on Rails and ReactJS later in the course. Both Rails and React use inheritance at a fundamental level, and our curriculum wouldn’t make sense without it. Moreover, inheritance is an important technique for building real-world software, and our graduates use it on a regular basis in the wild.

Whether inheritance should be taught to novices who don’t have an immediate need for it, for example in the first year of a 4-year university program in CS, is a different question. It’s also not a problem I’m being paid to solve / write a blog post about. We know that the curriculum we cover at Ada does need inheritance, so we can confidently move forward with our analysis.

What it Means to Teach Inheritance

I have heard using inheritance when writing software compared to using a lathe as a craftsperson. Both solve a certain class of problem extremely well, and neither is particularly useful if you don’t have that problem. Both lathes and inheritance take a fair bit of training to use well, and both are liable to make a big mess if used incorrectly. Every machine shop has a lathe, and most modern programming languages support inheritance.

The lathe metaphor allows us to break down the problem a little more. Thinking about it this way, we can see that any curriculum on inheritance needs to address two types of questions.

- How do you use inheritance? What specific syntax do you need, and how does that change the way information flows through your program? What rules do you need to keep in mind as you work (e.g. Liskov substitution, the open-closed principle)? These questions are more mechanical, and the answers are often language-specific.

- When should you use inheritance? How do you identify that a problem is likely to be neatly solved by inheritance, or that inheritance is a poor choice? What are the tradeoffs involved in deciding whether or not to use inheritance? These questions are more theoretical, and the answers are likely to apply no matter what language or framework you use.

Thinking about these questions leads us to two main issues that make teaching inheritance difficult:

- The syntax and semantics of inheritance are tricky

- Problems that are well-suited to inheritance are complex

Let’s dive into each of these a little deeper.

Programming with Inheritance is Tricky

One of the main reasons teaching inheritance is hard is because inheritance itself is hard. At a high level inheritance is easy to explain: one class gets all the code from another class, and can override pieces and add its own bits. As so often happens, the devil is in the details.

For example, with Ruby the following questions arise:

- Are static methods inherited? Can they be overridden?

- How are instance variables, class variables, and class-instance variables handled?

- Can constants be overridden? If not, what should you do instead?

- How does inheritance interact with nested classes?

- What has precedence, methods from the parent class or from a mixin?

And that’s for Ruby, which is supposed to be beginner friendly! Other languages have their own wildcards:

- Python: multiple inheritance

- JavaScript: prototypical inheritance model, multiple types of functions

- Java: static typing and explicit polymorphism, interfaces, templating

- C++: all the Java problems plus memory management and object slicing (shudder)

Whatever language you choose, there’s going to be a lot of rules to remember. How do you encode all these, especially for a novice? How do you decide what to include up-front, what to put in the appendix, what to omit entirely? How do you introduce specific details while still keeping the discussion general enough to translate to other languages? This is an important part of the problem – all your theoretical knowledge of how inheritance is used and what kinds of problems it solves won’t do you any good if you can’t apply it in code.

Fortunately, this part of the problem of teaching inheritance is well-understood. There are many excellent texts that round up the complicated syntax and semantics of inheritance into digestible, intuitive chunks. Any alternative treatment of inheritance needs to acknowledge this challenge and build upon this existing work.

Problems that Need Inheritance are Complex

The other reason that teaching inheritance is hard is because problems that benefit from inheritance tend to be complex. At a minimum, a problem to be solved with inheritance needs:

- Two or more domain objects that are similar enough they need to share code, but not so similar that they could be combined into one class

- Enough other things going on that it’s worth encapsulating the domain objects as classes in the first place

That’s a non-trivial amount of complexity, especially for a classroom full of beginners. How can you reasonably build a school project that establishes this complexity, but still fits within the tight time limits of the course? This is where existing curriculums tend to break down.

One tool that springs to mind to address this challenge is scaffolding, possibly by implementing some portion of a project in advance. This allows an instructor to reduce the complexity of the work required of the student, without reducing the complexity of the problem space as a whole. Deciding exactly what and how much to scaffold requires us to do a little more research, so we’ll come back to this problem later.

How is Inheritance Used?

Since Ada is a workforce development program, one of the most valuable things we can do is ask “what’s going on in industry?” Specifically,

- How is inheritance used in the real world?

- How is inheritance most likely to be used by a junior engineer in their first year or so on the job?

Understanding how inheritance is used can give us some direction on how it should be taught. Let’s look at a few examples.

Rails

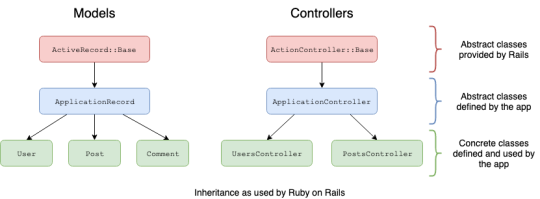

In Rails, almost every class you write will inherit from something. The two most common are

ActiveRecord::Basefor modelsActionController::Basefor controllers

You also see inheritance used for everything from database migrations to configuration management – its the Rails Way™. If you want to do something, you inherit from a class somewhere in the Rails framework. These superclasses are generally quite abstract, and each covers some functionality specific to the domain of an MVC framework.

Another important idiom is the template method pattern, as made famous in the Gang of Four book. A great example of this is with database migrations, where you define an class that inherits from ActiveRecord::Migration and implement the change method, and Rails takes care of the rest. Controller actions also mimic the template method pattern, particularly if your application uses the builtin tools for RESTful routing.

For the most part, Rails does not have you define your own superclasses. The exception to this is ApplicationRecord and ApplicationController, which sit in the hierarchy between concrete models or controllers and the abstract Rails implementation – these are generated automatically by Rails, but are open for you to modify.

React

React isn’t quite as broad in its use of inheritance as Rails. However, every component class inherits from React.Component.

In React we again see the template method pattern pop up. Whether you’re implementing render or componentDidMount, React knows the algorithm and you fill in the details.

React also does not encourage defining your own superclasses. In fact, their official documentation is rather explicit that inheritance between components should be avoided.

Other Frameworks

Rails and React are the two industry-grade frameworks I’m most familiar with, but I’ve dabbled in some others, namely Android (Java) and Unity (C#).

Android follows a similar pattern: everything you write inherits from some builtin class, template methods abound, and developers are discouraged from building their own inheritance relationships.

Unity matches the pattern as well, but they seem to be more lenient about extending your own classes, at least as far as I can tell from the Unity documentation on inheritance.

Industry Experience

This matches my experience of how engineering work tends to be done. Design work, in this case identifying the abstraction and building the superclass, is done by the team as a whole or by someone with an impressive sounding job title like “principal consulting systems architect”. Implementing the details in a subclass is the job of an individual engineer.

Concretely, as I was spinning up at Isilon I spent a lot of time working on C++ and Python classes that filled in the details of an existing pattern, and not a lot of time inventing new patterns. Template methods were something I used frequently without having a name for them, and which I later wished I had learned about in college.

Summary

| Setting | Use case | Write subclasses | Write superclasses | Abstract classes | Template methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rails | Web servers | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ |

| React | Single-page applications | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Android | Mobile apps | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Unity | Video games | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| First year in industry | Any or none of the above | ✅ | ❓ | ✅ | ✅ |

There are a few clear takeaways from this quick survey:

- Inheritance solves a complex problem. Programs that benefit from inheritance tend to be fairly large

- Writing a subclass is much more common than writing a superclass

- Often the superclass is provided for you by whatever framework you’re using

- Superclasses tend to be abstract, both semantically (embodying a high-level concept) and functionally (never instantiated)

- The template method pattern is extremely important

Existing Work

We’ve built an understanding of what a new engineer needs from an introduction to inheritance. How well does existing computer science curriculum match up with this?

Building Java Programs

We’ll use a case study to demonstrate: the excellent Building Java Programs: A Back to Basics Approach by Stuart Reges and Marty Stepp. This text is used by many introductory CS courses, including the University of Washington, as well as by AP CS classrooms supported by the TEALS program. My first exposure to the book was while teaching with TEALS back in 2014.

- Building Java Programs does an great job introducing the vocabulary and syntax of inheritance.

- The first example is different types of employees in an HR system. This is simple enough to demonstrate syntax while still somewhat plausible – not an easy balance to strike.

- The text includes a discussion of where inheritance is not appropriate, and the difference between is-a and has-a relationships.

- The chapter introduces interfaces, abstract classes and abstract methods, and the ability to override a method. However, it makes no mention of the template method pattern.

- The chapter finishes with a more complex example dealing with different types of stocks and assets.

- This is substantial enough that inheritance is an appropriate technique.

- In this example, the pieces at the top of the hierarchy are abstract (an interface and an abstract class), matching the pattern identified above.

- The book does not provide any context for how this code will be used. I would argue this is a major oversight. Writing code in a vacuum is fine for experienced engineers, but in my experience novices benefit from concrete examples of how code will be used from the “outside”. With inheritance in particular, this would demonstrate how polymorphism is useful.

- There is no mention of the idea of extending a class implemented by a framework.

In general Building Java Programs is excellent, and I have a tremendous amount of respect for Reges and Stepp. It certainly did a good job of preparing my students for the AP CS exam. However, it does not introduce inheritance as it is used in the real world, particularly by novice engineers. As far as I can tell this is typical of introductory CS courses – certainly my undergraduate education at Purdue followed a similar pattern.

Design Textbooks

There is another type of text that addresses inheritance: books on software design. Famous resources like Practical Object-Oriented Design: An Agile Primer Using Ruby (POODR) by Sandi Metz, or Design Patterns (the “Gang of Four” book) by Gamma, Helm, Johnson and Vlissides address software design more generally, employing inheritance as one tool among many.

However, these books are targeted at experienced engineers trying to up their game, not at novices learning their chosen language for the first time. Moreover they discuss design from a ground-up perspective, whereas an engineer beginning their career is likely to build on the shoulders of giants, extending existing designs rather than inventing new ones.

An ideal curriculum would bridge the gap between these two approaches, introducing both syntax and common inheritance idioms, and getting new engineers used to the work of extending an existing class.

Ada’s Approach to Inheritance

The instructional team at Ada has been unhappy with our approach to inheritance for a while now, but we haven’t quite known what to do about it. Now that we’ve done some research and formalized our engineering and pedagogical intuition, here’s the approach we’ve come up with:

- Simple examples and accessible metaphors are fine for introducing syntax and semantics, though as Reges and Stepp demonstrate they don’t have to be completely unrealistic.

- Common idioms like abstract classes and the template method pattern should be introduced as soon as the basic syntax is understood.

- Students’ first serious inheritance project should involve extending an existing superclass.

- This matches the way inheritance is used in the real world, and makes the benefits (not having to re-write a bunch of code) immediately clear.

- Instructors would provide the following scaffolding:

- Superclass implementation

- Driver code demonstrating polymorphism

- Another subclass, to model the inheritance mechanism

- Possibly a test suite or test stubs

- If time permits, a second inheritance project would focus on design, and have students build both the superclass and subclasses, as well as driver code.

At Ada, the first inheritance project takes the form of OO Ride Share. Students are asked to load information about drivers, passengers and trips from CSV files; we provide a CsvRecord superclass and Passenger and Trip subclasses pre-built. We feel this problem is complex enough to justify inheritance but simple enough to spin up on quickly. It also mimics the way ActiveRecord is used in Rails, which will hopefully lead to more comfort and deeper understanding once we get into our Rails unit.

The second project is still in the planning phase, but the idea is a command-line app that integrates with the Slack API. After an in-class design activity students will implement a Recipient superclass that handles most of the API interaction, and User and Channel subclasses that fill in the details. They will also build a command loop that interacts with the user, demonstrating the power of polymorphism. We don’t have the project write-up finished yet, but there is a prototype of the end product.

We’ve spent a lot of time thinking about this fresh approach to teaching inheritance, and I’m excited to see the results. Watch this space for an update in a couple months as we conclude our Intro to Ruby unit and move into Rails.